When those clever people first created and introduced plastic bottles soon after WW2 (1947), they must have thought they had a wonder product – and when PET bottles were introduced in the Seventies it must have seemed like the ultimate answer for fizzy drinks.

When those clever people first created and introduced plastic bottles soon after WW2 (1947), they must have thought they had a wonder product – and when PET bottles were introduced in the Seventies it must have seemed like the ultimate answer for fizzy drinks.

How wrong they were. Along with the inevitable small improvements in strength and weight we are about to undergo and entire sea change - with the potential of dramatically improved shelf life (possibly ten times longer for fizzy drinks) twinned with substantial improvements in quality and taste. The "Designer Coating," as I call it, revolution has already started and forms a close and surprising parallel with another major food revolution – Modified Atmosphere Packaging (MAP). It will change the way in which drinks are bottled and affects both fizzy and still drinks.

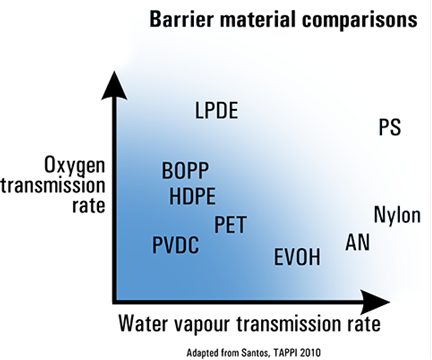

The link to MAP is not the modified atmosphere itself, but the much less widely understood concept of "permeability" which underlies them both. Permeability is the ability of a gas or vapour to flow through a solid material. With fizzy drinks this is usually the outflow of CO2 and inflow of oxygen. But if you think about fruit juices you will realise that the story gets a lot more complicated (in exactly the way it did with MAP) and if you then move on to drinks like beer the story becomes very complex indeed – with different and competing factors affecting many aspects of flavour, preservation and fizz.

Typical levels of carbonation

Volume |

g/l |

|

Lightly sparkling |

2.0 |

4 |

Carbonated fruit juice |

2.5 |

5 |

Lemonade |

3.0-3.5 |

6-7 |

Cola |

4.0 |

8 |

Mixer |

4.5-5.0 |

9-10 |

The "Designer Coating" revolution has already started. Many PET bottles are coated to improve strength and oxygen permeability. We have advanced coatings with a variety of names and processes – "Nano-bricks" (made from clay and polymers), Diamond-like carbon, CVD (Chemical Vapour Deposition) coatings, not to mention entirely new materials that are alternatives to PET. All of these are impressive steps forward, but to understand the next Designer Coating generation, you need to spend a little time understanding its key –permeability.

Permeability is simple to understand in principle – it is just the rate at which a vapour (e.g. water-vapour, CO2, oxygen, nitrogen) flows in or out of the bottle through its sides. The first complication is that the rates for different gases can be wildly different – for example PET is a good barrier against water vapour, but it is poor for oxygen, which it allows to flow in and spoil the product. For nitrogen and other vapours, the barrier properties are different again. And if you include temperature and pressure, where a change of 45oC changes oxygen through PET flow rates by a massive 2500% (at 50% RH), the story becomes ever more complex.

Lastly, when you realise that different drinks such as fruit juices, beer, tea, and sparkling water all need different factors to maintain their freshness, taste, carbonation and shelf life, the story becomes very complex indeed.

So it seems that PET is not quite the one-material-suits-all originally hoped for.

The solution, as with Modified Atmosphere Packaging, started with a range of new permeability controlling coatings and materials. The critical next stage will, I confidently predict, follow the same route towards individual "Custom Designed" coatings that keep drinks much longer and in better condition. Indeed, the extremely intricate demands of some beverages, such as different beers, could hardly be satisfied by anything less.

Up until the 1990s this would have been a technically and commercially unfeasible task as the way of measuring permeability involved sealing a small cup with the barrier material (in this case PET or PET plus coating), weighing it very accurately, then reweighing it weeks or months later to determine the tiny weight change caused by permeating vapour.

Fortunately, since then a new breed of devices ,including the ones we design and manufacture, use different measurement techniques which effectively count the rate at which individual molecules of gas permeate in or out. This not only cuts the timescale (and costs) from months down to a few hours (less in some cases) but the new detectors make measurements ever-more accurate and far less subject to error. The testing of different materials and coatings has become easy.

Unfortunately, just because you know the permeability of PET and a coating, does not mean you can calculate the permeability of a finished bottle. Factors such as manufacturing technique are important – for example blow moulding can easily reduce permeability by a factor of four, so it is essential to test the finished bottle.

There are four main influences (plus beverage specific ones) which are driving the market. The biggest is the loss of carbon dioxide – usually the main feature in both shelf life and quality. Around eighty per cent of CO2 is lost through permeation, with the remainder caused by factors including creep, sorption and leakage. Permeability is, in turn, dependent on the crystallinity and orientation of the plastic, stress, temperature, humidity, manufacture, wall thickness and viscosity.

The next driver is the problem of the flow of oxygen into the bottle, which reduces quality in several ways – it reacts with beverages that include vitamins (especially vitamin C) and also reacts with flavouring and colour components (especially under sunlight).

Next in importance is probably the loss of nitrogen, which can be used either to exclude oxygen – or to improve "taste" (this seems to work in a rather odd way related to bubble size – which I discuss in the next paragraph). Lastly there is water loss (or gain) which also has an effect on quality, especially for beverages that need controlled humidity to preserve freshness.

Actually people don't "taste" carbonation, they "feel" it, in the same way they feel pain. When CO2 leaves a bottle and lands on the tongue, it surges out of solution to mix with water and the carbonic anhydrase enzyme to form carbonic acid. When the concentration reaches a specific level, the tongue's pain receptors (nocireceptors) sends signals to the brain. Hence fizzy drinks leave a tingling sensation in the mouth after you have swallowed them. It is said that smaller bubbles, such as those created by Nitrogen, produce a softer feel in the mouth (e.g. Guinness' "Widget" which adds nitrogen bubbles as a can is opened). Although the science is inconclusive, personal experience leads me to think it is true.

It has been said that beer is almost the Holy Grail for the designer customisation of plastic bottles, as the structure of the flavours are individual to each brew and different ingredients have markedly different requirements to prevent, or at least delay them spoiling. Their carbonation depends on many factors, most common beers are carbonated by introducing CO2 under pressure but microbrews become naturally carbonated by the fermentation process.

The world has moved a long way since 1692 when Dom Pérignon, a French Benedictine monk, was (incorrectly) accredited with introducing sparkling drinks. Actually in-bottle refermentation was already a huge problem and any wine bottled in this state effectively turned into a time bomb!

Today, for the first time, we have the ability to custom-design both the materials from which a bottle is made and the coatings used (I hear of people working with up to nine separate coatings to fine tune the permeability for the gases and flavours involved). More importantly, we can quickly measure the most complicated material and bottles – testing a spectrum of coating formulas, structures and production techniques. The aim is a perfect customisation for every beverage and the prize is a big one – better, higher quality and tastier drinks that last many times longer.

And when this revolution, which has already started, arrives there can only be one response from both manufacturers and consumers – Cheers!